Locum tenens wasn’t as widely known in 1982, but neuro-hospitalist Dr. Andrew Wilner found himself working locums following a demanding residency program. During his time as a resident, he was forced to put his creative writing career on hold since he was essentially working seven days a week. “I decided I was going to undermine my performance as an intern by taking time out to do my writing,” he says.

Following internship, Dr. Wilner decided to take a year off to regroup and pick up where he left off with writing. And it was during this sabbatical that he chanced upon locum tenens work.

“I found an emergency room nearby where other residents were moonlighting, and next thing I know I was working a 36-hour work week as the only physician in this very small, 83-bed hospital,” he recalls. “I worked three 12-hour shifts a week, so I was able to have a few days to focus on my writing.”

Discovering a love for neurology

During his time working locum tenens in the 1980s, Dr. Wilner soon discovered he was most interested in the patients presenting with neurological symptoms. He would always observe the consultation and work-up of the on-call neurologist when they’d come in to help diagnose the patient.

“They’d come into the ER for the consultation and perform a more elaborate physical exam than what I was familiar with, and I’d think that was pretty cool,” he says. “So this assignment paved the way to becoming a neurologist. This eventually led me to applying to a neurology program, where I ended up becoming a neurologist and internist.”

The intersection of two passions

Once he knew he wanted to focus on epilepsy as a subspecialty, he helped establish a facility which specialized in epilepsy disorders. After eight years, he found his career path evolving into one of a medical journalist and keynote speaker.

“But after a while, I felt my skills as a clinician were becoming a little stale,” he says. “And because I hadn’t been seeing patients for half a dozen years, drug companies weren’t coming to me to be their spokesperson as much.”

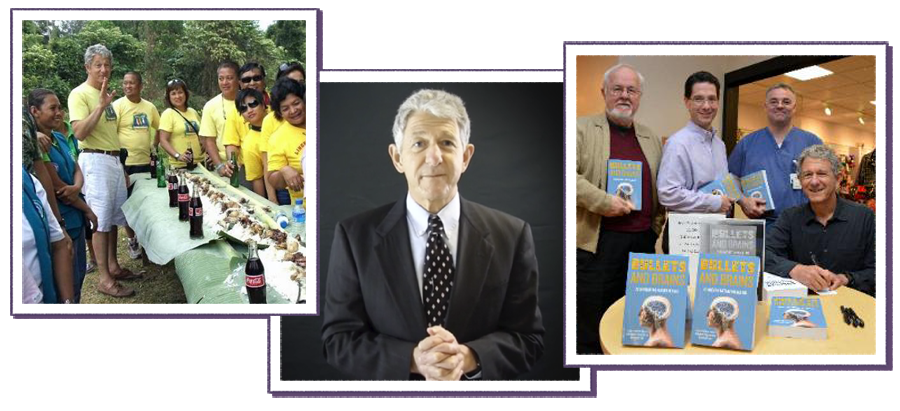

It was at this point that Dr. Wilner returned to practicing medicine by becoming a medical volunteer in the Philippines, where he became the medical director of a private practice group whose focus was medical missionary work — and where he met his wife.

A solution to burnout

“I got a job as a neuro-hospitalist, which was a new thing back then,” he says. “This was after 10 years as a medical journalist, so I had to jump through quite a few hoops to get back into clinical medicine. I found one hospital willing to accommodate me, and after working supervised rounds for two weeks I was good to go.”

After a year of one week at the hospital, then writing for medical journals on his off week, his schedule became untenable. He didn’t want to give up his writing, but without a change he was facing burnout. That’s when locum tenens entered his life again, and it turned out to be the perfect solution.

Using locum tenens to do it all

By switching to locums work, Dr. Wilner was able to continue his medical mission work in the Philippines. He could dictate his own schedule, which meant he could make his home in the Philippines and work assignments stateside in a six-months on, six-months off rotation. He was also finally able to pursue all of his life’s passions.

“I would work about six months a year so I was able to make enough money to continue writing. I also finally had time to become a PADI divemaster, where I could dive as much as I wanted. I learned how to do underwater video and I won a couple of awards for my films.”

Not only could he realize his dreams outside of academia, but locums allowed him the time to write a total of four books: Bullets and Brains, Epilepsy: 199 Answers, 3rd Edition, Epilepsy in Clinical Practice, and in 2018, he published The Locum Life, an insider’s guide to locum tenens.

The rewards of controlling your own destiny

When Dr. Wilner chose to return to permanent employment, the knowledge that he could return to locums work at any time gave him the confidence to negotiate the pay and schedule he wanted.

“I was sent an offer with a salary nowhere near what I wanted, so I told them I wouldn’t consider it,” he recalls. “The beauty of it was locums gave me the security to walk away from the deal — I’d have never been able to do that prior to working locums.

“With locums as a fallback I had all the time in the world to find a job and the leverage to negotiate because I knew what I was worth as a neurologist,” he says. “I knew what I earned, I knew what I was worth, and I had the freedom to say no.”

Once he’d established his expectations for his desired pay and schedule, the facility came back with an offer that had the pay he wanted and an ideal schedule that would allow him to continue to pursue his first love: writing.

“If you had told me 10 years ago while in private practice that I’d have the time and freedom to do all these things, I would have told you it was a pipe dream.”

Dr. Wilner is proof that dreams can come true.

You can learn more about Dr. Wilner’s career at www.andrewwilner.com.